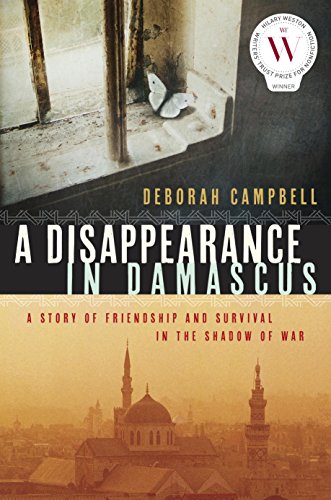

A Disappearance in Damascus: A Story of Friendship and Survival in the Shadow of War

from amazon.com

Winner of the Hilary Weston Writers' Trust Prize for Non-Fiction.

In the midst of an unfolding international crisis, the renowned journalist Deborah Campbell finds herself swept up in the mysterious disappearance of Ahlam, her guide, "fixer," and friend. Her frank, personal account of her journey to rescue her, and the triumph of friendship and courage over terrorism, is as riveting as it is illuminating.

The story begins in 2007 when Deborah Campbell travels undercover to Damascus to report on the exodus of Iraqis into Syria following the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. There she meets and hires Ahlam, a refugee working as a “fixer”—providing Western media with trustworthy information and contacts to help get the news out. Ahlam, who fled her home in Iraq after being kidnapped while running a humanitarian centre, not only supports her husband and two children through her work with foreign journalists but is setting up a makeshift school for displaced girls. She has become a charismatic, unofficial leader of the refugee community in Damascus, and Campbell is inspired by her determination to create something good amid so much suffering. Ahlam soon becomes her friend as well as her guide. But one morning Ahlam is seized from her home in front of Campbell’s eyes. Haunted by the prospect that their work together has led to her friend’s arrest, Campbell spends the months that follow desperately trying to find her—all the while fearing she could be next.

Through its compelling story of two women caught up in the shadowy politics behind today’s conflict, A Disappearance in Damascus reminds us of the courage of those who risk their lives to bring us the world’s news.

https://www.amazon.com/Disappearance-Damascus-Friendship-Survival-Shadow-ebook/dp/B00R04GCQU

Author: Deborah Campbell

Deborah Campbell is an award-winning writer known for combining culturally immersive fieldwork with literary journalism in places such as Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, Qatar, the UAE, Israel, Palestine, Cuba, Mexico and Russia. Her work has appeared in Harper’s, the Economist, Foreign Policy, the Guardian, New Scientist, Ms., and other publications. Her writing has been published in 11 countries and six languages. Her latest book, A Disappearance in Damascus, won the 2016 Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Prize, Canada’s largest literary award for nonfiction. The jury citation called it “a riveting tale of courage, loss, love, and friendship.” It also won the Freedom to Read Award and the Hubert Evans Prize.

She has won three National Magazine Awards for her foreign correspondence. Besides Middle Eastern Studies, her academic interests include languages, politics and history. She has guest lectured at Harvard, Berkeley and Zayed University in Dubai. She teaches at the University of British Columbia.

Reviewed by: John Stokdijk

A Disappearance in Damascus: A Story of Friendship and Survival in the Shadow of War by Deborah Campbell is the 2016 winner of Canada’s largest prize for literary excellence in the category of nonfiction. I am grateful to the Ajijic Book Club member who made us aware of this book as otherwise I would probably never have read it. My wish list of books to read is always growing but many good books inevitably escape my notice.

The book tells the story of Ahlam whose last name we never learn for very good reasons. She was an Iraqi refugee living in Damascus and it was there that the author met Ahlam in 2007. What follows is quite a story!

Today Syria is often in the news because it is currently suffering through a terrible civil war. But other than that I know little about modern Syrian history. Campbell provides some background relevant to the story, describing conditions hard to imagine, horrendous but later getting even worse.

It was the peak of Iraq’s civil war, and absolutely no one was travelling into Iraq on a happy journey; a million and a half refugees had already fled the other way, to Syria, and they were happy for nothing but to be alive.

Damascus— holding out the promise of salvation by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, or UNHCR— was swelling with the largest migration the region had ever seen. There was concern that the Iraqis would bring their war along with them. If that happened, it could tear Syria apart.

Deborah Campbell undertakes a style of journalism that is refreshingly different from what is fed to us by the mainstream media.

While most reporting focuses on those who “make history,” what interests me more are the ordinary people who have to live it. I wanted to put a human face to the war. As an immersive journalist, my work, the work I love, involves getting as close as I can for long periods of time to the societies I cover, most recently six months in Iran. But that was not possible for me to do inside Iraq. So I had come to Syria to meet the eyewitnesses...

To do her work Campbell requires the services of a “fixer” and finds Ahlam, an eyewitness to what happened in Iraq. I found it difficult to not be angry with the American government decision to invade Iraq in 2003, a mistake of historic proportions similar to Vietnam. It is easy to understand Americans now living here in Ajijic who left their own country in disgust during the Bush Presidency. The American government greatly contributed to making a very bad situation worse.

The story of Ahlam includes losing a son, being kidnapped, fleeing Iraq and being jailed and tortured in Damascus. With the help of the UNHRC and others, in 2008 Ahlam makes it to America. Campbell writes,

I should end the story here. Happy ever after in the land of opportunity.

But happily ever after is for works of fiction. It would be almost unbelievable if Ahlam did not suffer from PTSD. It was gratifying to read that her children are doing well and I will probably wonder how Ahlam is doing for quite a while.

As a small subplot in the book, Deborah Campbell shares a few insights into her own intimate relationships, helping us realize a tiny bit of human complexity.

I was hesitant to burden her (Ahlam) with my concerns. The gradual demise of a long relationship that showed obvious signs of deterioration whenever I was in the field for too long, and nagged at me even as I ignored it, was petty by comparison to what she dealt with every day.

I spent some time reviewing the notes at the end of the book which document some of the relevant history, the ugly history, that is the backdrop to the story of Ahlam and Deborah Campbell. Saddam Hussein, George Bush, Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz, Paul Bremer and others will be controversial historical characters in the bloody story of the Middle East for decades to come.

Reviewed by: Karl Homann

A Disappearance in Damascus: Friendship and Survival in the Shadow of War – Author Deborah Campbell

Review by Karl Homann

War does not determine who is right - only who is left.

Bertrand Russell

With regret, Deborah Campbell comments at one point of the book about her own journalistic effort:

I could accept the knowledge that nothing I wrote or would ever write would change a thing and that the world would continue to create and destroy and create and destroy as it always did.

Unfortunately, the author may be right, despite the “immersion journalism”, which she practices, as compared to, what she calls “parachute journalism” - the flying in and out, taking a couple of photos, interviewing two or three locals, and thus thinking you were an expert when you could have written the same thing without leaving the office.

Today, between talking points, superficial verbiage masquerading as “news” that fills the time between commercials and cable “headline news” which is endlessly picked apart by ideologically opposed “analysts”, there is no time or taste today for the kind of tenacious in-depth reporting which Deborah Campbell writes.

Today, we watch war on our TVs as if it were a video game: a little square on a drone’s radar screen homing in on its target, followed by a huge cloud of dust. No close-ups, no ear-splitting screams, no blood and guts spilled on a concrete side walk. Neat, clean and antiseptic, far away and somewhere else. And then we go back to munching our pop corn and watching skin care commercials in the smug belief that among the children and the elderly and sick, we may have killed a couple of bad guys of our own making.

However, there is no escape from Campbell’s passionate and searing account of the 1.2 million of Iraqi refugees fleeing the brutal and unjust war to seek fragile refuge in Syria. There is no escape from the pain and suffering and injustices of these refugees, personified in a charismatic Iraqi woman, named Ahlam, who becomes Campbell’s “fixer” – a go-between for the Canadian “undercover” journalist and her sources – and, eventually, her friend.

When Ahlam refuses to cooperate with the Syrian Secret Police, she is kidnapped, thrown in jail and beaten. Campbell courageously returns to Syria at her own peril and spends months desperately trying to find and free her friend.

There is no substitute for the suffering of an individual that brings home the folly and brutality of war. We cannot get our heads around the thousands or the millions affected by war - the numbers are too great - but the personal encounter with one or two or three of its victims perhaps gets our attention.

It has happened to me before when I visited the US Civil War memorial site in Vicksburg, Mississippi. Emotionally, I felt nothing for the thousands who had been killed or wounded or displaced. I only had intellectual curiosity. But when I came upon a clearing in a Mississippi wood with only three graves of confederate soldiers from the small town nearby, I felt the enormity of pain inflicted by this fratricidal war.

And so it is with A Disappearance in Damascus: Ahmal’s story and her struggle to do good in a world of madness emotionally gripped me and brought home to me the insanity of the Iraqi war, or any war for that matter.

P. S. Deborah Campbell mentions at one point that the Syrian government was afraid that the war of Iraq would follow the refugees and, indeed, it did.

- Here is also an email I received earlier from Deborah Campbell, in which she comments about our Ajijic Book Club website and her book, which we will be discussing in January. Check out Deborah's website.

From: Deborah Campbell

To: "Karl Homann"

Subject: A DISAPPEARANCE IN DAMASCUS

Dear Karl,

What a lovely email and website. It's a good thing you are doing.

It seems more important than ever to engage in this civil dialogue. And it seems to me that, in this time of simplification and polarization, books are one of the few places left where complex conversations can still take place.

In writing A DISAPPEARANCE IN DAMASCUS, I wanted to achieve something John Berger said in an interview shortly before he died: "What two different people have in common will always, in all cases, be larger than what differentiates them." These differences start diminishing as soon as we can see one another as complicated human beings.

My fixer, Ahlam, who became the subject of my book, is my friend today because we are much more the same than we are different. She's probably just a bit more badass than I am.

All my best, to you and your book group. I dream of spending more time in Mexico...

Deborah

Deborah Campbell

www.deborahcampbell.org

“A seamless blend of storytelling and reportage. . .. A riveting tale of courage, loss, love and friendship.” —Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Non-Fiction Prize

In addition to my review, here are a couple of internet links with interviews given by the author; both worth watching, and have been aired on US TV:

https://www.mgshow.org/ Featured Interview

_A Disappearance in Damascus_ - Conversation with Deborah Campbell.mp4

https://www.c-span.org/ September 17, 2017

Panel Discussion on Refugees with Deborah Campbell

//www.c-span.org/video/?433414-12/panel-discussion-refugees

Reviewed by: Karl Homann

The CV of the author is rather scarce:

Lewis Richmond has been a Zen priest and meditation teacher (a role from which he has recently retired), and software entrepreneur. He remains an author, a musician and composer, a piano and composition teacher, and an editor and mentor to other authors.

Amazon.com

So, does that qualify him to write with authority about aging? Perhaps, but I found his book, Aging as a Spiritual Experience fairly light-weight. None of the examples of other cases mentioned in Richmond’s book applied to me, either because I am beyond their age, including that of the author, or because their personal circumstances of work, life and family were different from my own. His writing is not particularly inspiring either. I certainly would not consider him as editor or mentor of my own writing. I also did not care for the references to his being a Zen “priest” and the later chapter on Buddhism. Sitting around in an ochre-coloured gown, half naked, under a Mahabodhi (fig) tree just isn’t my stick.

“Everything changes” (Buddha). I knew that already. Others say, you are only as old as you feel. Silly aphorisms like that which pretend to express a general truth just don’t do it for me.

I AM old, and I feel it. No doubt about it. I feel the pain in my bones. Every morning when I wake up, I am surprised that I am still alive and feel slightly depressed about it, until after I have had my shower and a double Expresso coffee.

With that said, though I do not “meditate”, I do reflect, and Richmond’s book gave me the chance to reflect on my past life, mostly at night before falling asleep. And in my reflections, I realized, perhaps for the first time, that my life had been a succession of survivals: surviving a war, the death of my family, the anger of my father, an unhappy adolescence, three years as a monk, a chronic illness, the losses and sadness of the break-down of three marriages, an addiction to alcohol (driving at 160 km an hour and throwing the bottles out of the window), a machete attack on a Caribbean island, and starting a new life four times in a different country.

I also found that I did not have any elders in my life who could have helped me understand the aging process because all of them died before I needed them. I was, however, present at the side of my two mothers, when they exhaled their last breath and died, one violently and one due to illness. So, I wondered, how, when and where will I die and what happens afterwards.

Once I asked a good friend, a priest, ten years my elder:

He, himself, died a year afterwards, peacefully, in his sleep.

So, I keep breathing in and out in order to survive until I die. Until then, I hold with the incisive words of Dylan Thomas, poet, who died at the age of 39:

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning, they

Do not go gentle into that good night….

Reviewed by: Karl Homann

In The New Tsar: The Rise and Reign of Vladimir Putin (Aug 23, 2016), Steven Lee Myers recounts Putin's public life --from his childhood of abject poverty in Leningrad to his ascent through the ranks of the KGB, and his eventual consolidation of rule in the Kremlin. (Amazon.com)

A Man Named Vladimir

Review by Karl Homann

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin, that is, the four-time President of the Russian Federation and Commander-in- Chief of the Russian Armed Forces.

Putin has served as President of Russia from 2000 to 2008 and again since 2012. In between his presidencies, he was Prime Minister of Russia. On March 18, 2018, he was re-elected as president with 77% of the popular vote, although his popularity has declined somewhat to just above 60%, given the drop in petroleum and natural gas prizes, of which Russia is a major exporter. When Putin steps down in 2024, he will barely have reached the age of 72

But WHO is this man, named Vladimir Putin, a question that was not only asked by foreign leaders and commentaries when he suddenly appeared on the political scene in 2000 as a protegee of Boris Yeltsin, the first President of the Russian Federation (1991 to 1999), but by Muscovites themselves.

The New Tsar: The Rise and Reign of Vladimir Putin (Aug 23, 2016) by Steven Lee Myers in his Putin biography provides some of the answers, though, at times, skewed by the writer’s western perspective. Myers gives a succinct answer at the very end of the biography, as Putin inevitably and unchallenged cruises towards his fourth presidency:

No Putin, no Russia.

And that will, indeed, be the case until 2024.

****

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin was born on October 7, 1952 in Leningrad (today, Saint Petersburg), the third son of the elder Vladimir, who worked in a railroad carriage factory, and was a member of the Communist Party. His mother Maria was forty-one years old when she gave birth to her son. They lived in one room of a communal, rat-infested apartment; no hot water, no bathtub, only a communal kitchen and bathroom, which they shared with two other families.

“We lived simply - cabbage soup, cutlets, pancakes, but on Sundays and holidays my Mom would bake very delicious pirozhki, stuffed buns with cabbage, meat and rice, and vatrushki, cottage cheese tarts.”

An elderly Jewish couple became his surrogate grandparents, and ever since, Putin holds a strong disdain for all religious intolerance, especially anti-Semitism. At school, he was bullied for his size but learned martial arts to defend himself. According to his teachers, he was an indifferent student, petulant, disruptive, and the only one among 45 classmates who did not join the Communist Youth organization.

“I was a hooligan, not a Pioneer,” he wrote later.

In fact, Putin never became or was a member of the Communist Party, but popular Russian espionage novels and movies of the 60’s inspired him to join the KGB. Young Vladimir tried three times to find the right entrance to the KGB “Big House” in Leningrad, before an officer flatly told him that the KGB did not accept volunteers. To get rid of the young man, the officer suggested that he attend law school. So, against the wishes of his parents, Vladimir enrolled in the university law school in the fall of 1970. He also continued his studies of the German language, which he still speaks fluently today.

During the summer, he attended judo competitions, cut timber, worked in construction camps, and once earned 800 rubles, with which he bought a coat that he wore for the next fifteen years.

In the summer of 1975, he finally fulfilled his childhood dream of joining the KGB, which by this time had grown into a vast bureaucracy. Putin was assigned to the personnel office, not exactly what his childhood imagination had hoped for. But luck was on his side when the former KGB chairman Yuri Andropov became the supreme leader of the Soviet Union and sought to reform the Soviet system, especially in economic affairs and international relations.

As if he had anticipated it, Putin had written a thesis on the principle of “most-favored-nation status in international trade” during his study at the Leningrad State University. He, therefore, was transferred to the elite branch of the KGB, the Directorate responsible for intelligence operations beyond the Soviet Union’s borders. But once again, he was assigned rather routine tasks such as monitoring religious Easter processions. When a friend asked him what it meant to be an “intelligence officer”, Vladimir answered,

“I am a specialist in human relations.”

In 1979, with the rank of captain, he attended the KGB Academy in Moscow, whose training manual described an intelligence officer’s characteristics as having “a warm heart, a cool head, and clean hands.”

From 1985 to 1990, he served in Dresden, East Germany, undercover as Mr. Adamov, the director of the Soviet-German House of Friendship, a social and cultural club.

Personal note: As a high school student, my class visited one of these centres in East Berlin in 1960, one year before the Wall, where we discussed the benefits and/or disadvantages of the capitalist versus the socialist political system with our East German counterparts.

Putin genuinely enjoyed spending time in Germany, and he respected the German culture. According to Putin's official biography, during the fall of the Berlin Wall (1989), he burned KGB files to prevent demonstrators from obtaining them. Then he confronted the angry mob, alone, and talked them out of storming the building.

At age 28, still a bachelor, Putin met Lyudmila Shkrebneva, a blue-eyed stewardess with Aeroflot. Whenever she asked what he did during the day, he evaded her questions with jokes like:

“We go fishing all day. Before lunch, we catch. After lunch, we release.”

Her, however, he did not release.

In April 1983, on a trip to the Black Sea and Crimea, he hinted that in three and a half years, she had probably made up her mind. “Yes,” she said. He replied: “Well, then, if that’s the way it is, I love you and propose that we get married.” Vladimir and Lyudmila stayed married for 30 years and had two daughters, but almost nothing is known about Mariya, 33 and Yekaterina, 31. As adults, they have never been photographed by the Russian media, and it has been said that the Russian public would not recognize the women if they ran into them on the street. The girls have always been carefully guarded by the Russian government and were even pulled out of school and taught at home once their father hit the spotlight.

Two articles, one in BUSINESS INSIDER, August 28, 2012, and an investigative report by Reuters in 2015, tried to dig up some details, but had to admit that much of what they found was unconfirmed speculation and social media gossip.

Much the same can be said about Putin himself. While his public life and career are well-documented, little is known about his private life. We know that he loves sports:

“I just love everything new. I enjoy learning new things. The process itself gives me great pleasure.”

He skies, plays ice hockey, rides horses, scuba dives. He flies air planes from ultralights to guide Siberian white cranes on their migration route south, fighter planes for fun and water bombers to put out forest fires. He also takes a keen interest in animal protection programs: Amur Tigers, Beluga Whales, Polar Bears, and Snow Leopards.

His mother has said that Vladimir loves his daughters, but Putin also loves dogs, perhaps, even more than his daughters.

“The more people I know, the more I love dogs,” says Putin.

His beloved black Labrador Konni died in 2014. Once answering a question at a press conference, Putin stated that, like everyone else, he, too, can be in a bad mood: "In those moments, I consult with my dog Konni, who gives me good advice."

Konni has since been replaced with other puppies, the gifts of political leaders: Buffy, a Bulgarian Shepherd; Yume, an Akita, as thanks for Russia’s help with a Japanese earthquake in 2011; an Alabai puppy from Turkmenistan, named Verny (or “Faithful”) in Russian.

Little else is affirmatively known about Putin’s private life. Apart from social media gossip, he remains an enigma. But a 2017 Business Insider article gives us a glimpse of his working life.

He rises late; has breakfast at noon. Next, he takes time to exercise. Newsweek reports that Putin spends about two hours swimming, one at noon, another at midnight. According to Putin, when he is in the water, he "gets much of his thinking about Russia done”. After his swim, Putin lifts weights in the gym. As we know from photos – some real, some photo shopped – the 66-year-old has, over the years, cultivated a “macho” image.

When he gets to work in the early afternoon, he reads his briefing notes, reports on domestic and foreign affairs, as well as clips from the Russian press and the international media. He is extremely well-informed on all political matters, domestic and foreign.

Occasionally, Putin will watch a satirical online video mocking him and his government. Otherwise, he abstains from most technology at work, preferring "red folders with paper documents, and fixed-line Soviet War Era telephones" to computers.

No hacking, no tweets!

The Russian president stays up until midnight working. And so must his staff and advisers, one of whom says that Putin is a modest man, soft-spoken who waits his turn to speak. But when he speaks, he speaks with authority and is very articulate. He vigorously confronts any inefficiency and incompetence in his ministers, firing them openly or suggesting that they resign, if they are not capable of handling their job.

NOTE: Putin’s rather unusual work schedule may have something to with the former 11 and present 9 time zones.

Putin doesn’t drink alcohol, except a little at formal receptions. According to Politico, the Russian President may be taking a symbolic stand amid Russia’s widespread alcoholism and wishes to separate himself from his drunken predecessor Boris Yeltsin.

Over the weekend, he leaves time for his English classes, and on Sunday he sometimes goes to church and to confession, although those close to him stress that “his life is not that of an Orthodox Christian.”

When Putin took on the Russian presidency for the first time (2000), he inherited a country that was run by eight oligarchs who controlled almost 50 percent of Russia’s GDP, in companies gifted by Boris Yeltsin for political support (sort of a Russian form of “Citizens United”). In February 2003, Putin called them all together and told them:

There will be no more oligarchs. If you are unhappy with that, you have only yourselves to blame.

I have watched a Russian video of Putin flying halfway across the country to meet with the owners of a factory which they were planning to close. He called them “cockroaches” and put a contract in front of them to keep the factory open. When the main oligarch owner lied about having signed, Putin said, “I don’t see your signature.” Then he gave him a pen, pointed to the spot of the document: “Sign here”, and after he had signed, he walked away while putting Putin’s pen in his pocket, Putin called him back, saying “Now give me my pen back.”

While some might argue that Putin’s leadership does not reflect a specific ideology, Chris Miller (Assistant Professor at The Fletcher School and author of Putinomics: Power and Money in Resurgent Russia) has discerned three beliefs which are consistent with Putin’s political pronouncements and actions.

When Putin began his political career, the former Soviet Union was unable to effectively collect taxes or provide services, therefore…

1. Putin believes that the government needed a strong centralized control of the vast empire (then 11, now 9 time zones). To maintain that central control has been his highest priority.

2. Second, to keep the populace supportive of his government and thus to prevent revolt, Putin believes that the key is rising wages and pensions.

3. Third, economic progress depends heavily on private enterprises but only so long as those enterprises (or oligarchs) do not interfere with either central government control or rising salaries and pensions. Whenever a private enterprise violates either of first two beliefs, then the government takes control of the enterprise.

Whoever does not miss the Soviet Union has no heart. Whoever wants it back has no brain. (Vladimir Putin)

Putin wanted to make Russia strong again and reconnect it with the West. But after several attempts and many rejections, he just does not seem to care any longer whether the West wants a relationship with Russia or not.

Today, Russia’s economy has stabilized, inflation is at historic low, the budget is nearly balanced. Gazprom, Russia’s largest natural gas exporter, has again increased its deliveries to Europe. The Russian share of the European gas market increased to 34 percent last year. Ironically, even the remaining 20 US military installations in Germany are heated by Russian natural gas.

At a summit in June 2001, in Slovenia, George W. Bush said,

“[Putin] is a man deeply committed to his country…. I looked the man in the eye. I found him very straightforward and trustworthy – I was able to get a sense of his soul."

The relationship between Bush and Putin, however, soured, once the US invaded Iraq.

Did Trump in Helsinki get a sense of Putin’s soul? – Why would he? Or should that be, why wouldn’t he?

Hilary Clinton remarked in one of her loosing electoral debates: Putin was a KGB agent and this, by definition, means that he has “no soul”. Would she say the same about her successor, Secretary of State, Mike “Top CIA Spy” Pompeo? That he, too, has no soul.

According to Putin, the United States must respect another country’s interests and not change the rules whenever it suits them:

THE ECONOMIST - Feb 4th, 2016

VLADIMIR PUTIN seems impervious to the woes that afflict normal leaders. His approval rating stayed at slightly above 80% (2016), but has since fallen to slightly above 60% (2018). For his fans, Mr. Putin’s shock-resistant ratings serve as proof of his righteousness.

Some Russian liberals and Western observers have claimed that there is something wrong with the polls. But the independent Levada Centre records approval levels for Mr. Putin similar to those of state pollsters; and so does the in-house sociological service of Alexei Navalny, an opposition leader, whom The Wall Street Journal has described as "the man Vladimir Putin fears most."