The Great Unknown: Seven Journeys to the Frontiers of Science

from amazon.com

A captivating journey to the outer reaches of human knowledge

Ever since the dawn of civilization we have been driven by a desire to know--to understand the physical world and the laws of nature. But are there limits to human knowledge? Are some things beyond the predictive powers of science, or are those challenges simply the next big discovery waiting to happen?

Marcus du Sautoy takes us into the minds of science's greatest innovators and reminds us that major breakthroughs were often ridiculed at the time of their discovery. Then he carries us on a whirlwind tour of seven "Edges" of knowledge - inviting us to consider the problems in quantum physics, cosmology, probability and neuroscience that continue to bedevil scientists who are at the front of their fields. He grounds his personal exploration of some of science's thorniest questions in simple concepts like the roll of dice, the notes of a cello, or how a clock measures time.

Exhilarating, mind-bending, and compulsively readable, The Great Unknown challenges us to think in new ways about every aspect of the known world as it invites us to consider big questions - about who we are and the nature of God - that no one has yet managed to answer definitively.

https://www.amazon.com/Great-Seven-Journeys-Frontiers-Science-ebook/dp/B01IOHQ8P6

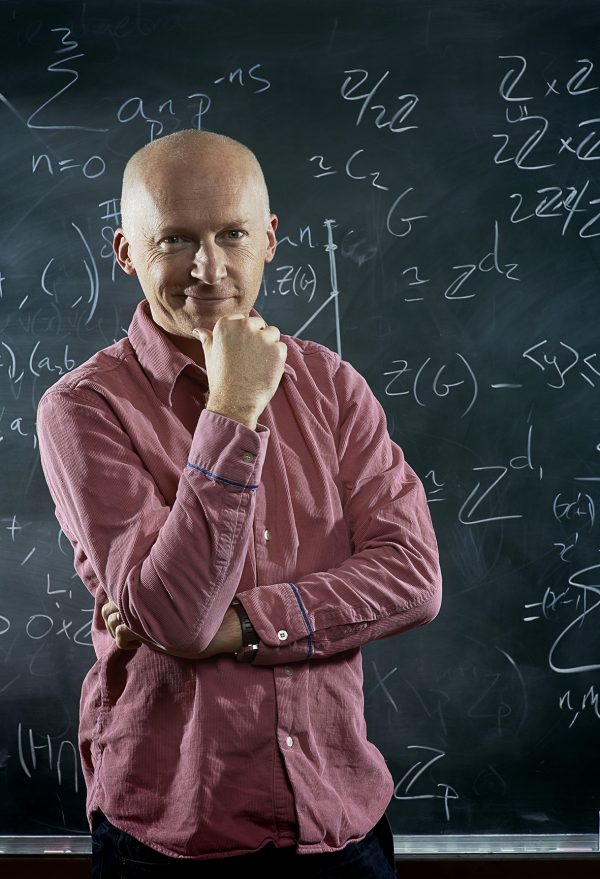

Author: Marcus du Sautoy

Marcus du Sautoy is the Charles Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science at the Oxford University, a chair he holds jointly at the Department of Continuing Education and the Mathematical Institute. He is also a Professor of Mathematics and a Fellow of New College. He was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 2016. In 2001 he won the prestigious Berwick Prize of the London Mathematical Society awarded every two years to reward the best mathematical research made by a mathematician under 40. In 2004 Esquire Magazine chose him as one of the 100 most influential people under 40 in Britain and in 2008 he was included in the prestigious directory Who’s Who. In 2009 he was awarded the Royal Society’s Faraday Prize, the UK’s premier award for excellence in communicating science. He received an OBE for services to science in the 2010 New Year’s Honours List. He also received the Joint Policy for Mathematics Board Communications Award for 2010 and the London Mathematical Society Zeeman Medal for 2014 for promotion of mathematics to the public.

Reviewed by: John Stokdijk

The Great Unknown: Seven Journeys to the Frontiers of Science by Marcus du Sautoy is a difficult book, even more difficult than I expected. Marcus du Sautoy is a mathematician and this shapes his approach to his chosen subject. He loves math and this itself was something I found interesting but it is not a passion I share. But I plowed through the book and I was often rewarded for my effort by his insights.

My own mathematical research is already pushing the limits of what my human brain feels capable of understanding… My new role as the Professor for the Public Understanding of Science has pushed me outside the comfort zone of mathematics into the messy concepts of neuroscience, the slippery ideas of philosophy, the unfounded theories of physics. It has required a way of thinking that is alien to my mathematical mode of thought, which deals in certainties, proofs, and precision. My attempts to understand everything currently regarded as scientific knowledge have severely tested the limits of my own ability to understand.

Marcus du Sautoy is far more intelligent and much better educated than I am. However, I share his desire to test the limits of my own ability to understand the messy concepts he confronts. My desire to learn motivates me to read books like this from time to time.

I will now jump to the conclusions du Sautoy reaches at the end of his book.

So, at the end of my journey to the edges of knowledge, have I found things that we can categorically say we cannot know?

What we cannot know creates the space for myth, for stories, for imagination, as much as for science. We may not know, but that doesn’t stop us from creating stories, and these stories are crucial in providing the material for what one day might be known. Without stories, we wouldn’t have any science at all.

It is important to recognize that we must live with uncertainty, with the unknown, the unknowable.

All seven journeys to the edge of current knowledge are interesting but three of them are particularly so to me. In each journey du Sautoy gives the history of the progression of knowledge up to today. In each case he attempts to identify what is unknown but knowable as well as what may never be known.

What do we know about matter? Today the edge of knowledge takes us to three fundamental particles: the up quark, the down quark, and the strange quark. Questions remain.

Are the quarks that Franklin helped discover the final frontier, or might they one day divide into even smaller pieces, just as the atom broke into electrons, protons, and neutrons, which in turn broke into quarks? ...Will we ever find ourselves at the point at which there are no new layers of reality to reveal?

Does quantum physics have the answers?

One of the big unknowns is this: Why is there something rather than nothing?

… you do at least need a stage on which to play this quantum game. Some equate empty space with nothing. But that is a mistake. Three-dimensional empty space, a vacuum, is still something. It is an arena in which geometry, mathematics, and physics can play out. After all, the fact that you have a three-dimensional rather than a four-dimensional empty space already hints at the evidence of something. Nothing does not have a dimension. The ultimate challenge, therefore, is to explain how quantum fluctuations might produce space and time out of genuine nothingness.

Marcus du Sautoy confirms a conclusion that I reached several years ago. Why is there something rather than nothing is a question that probably will remain unanswerable for a very long time, possibly forever. My answer to the question is I DO NOT KNOW and I am not persuaded by those who assert dogmatic answers to this very important question.

The history of the science of consciousness is quite different than the other histories covered in the book because neuroscience is a very young field of research which accelerated dramatically about twenty-five years ago with the advent of the fMRI scanner.

We are in a golden age for the question of consciousness… Neuroscientist Christof Koch showed me another striking example of how the brain processes visual data in surprising ways. Koch is one of the leading lights in the modern investigation into consciousness… neuroscientist Giulio Tononi … the “hard problem,” as philosopher David Chalmers famously put it, of getting inside another person’s head… Daniel Dennett is one of the most famous of the modern-day philosophers… As we finished our Skype chat, Koch conceded that there was no guarantee we would ever know how to determine consciousness.

Koch, Tononi, Chalmers, Dennett are people with whom I am somewhat familiar with. The mystery of consciousness is, in my opinion, one of the great, enduring mysteries facing human beings. Perhaps Marcus du Sautoy has taken his readers to the edge of neuroscience but, in my view, he does not take his readers to the edge of all knowledge about consciousness.

There are three other books which I have read that relate to the themes in The Great Unknown and all were easier to read and understand.

The book The Island of Knowledge: The Limits of Science and the Search for Meaning by Marcelo Gleiser makes a far less optimistic case about what is unknowable than The Great Unknown. I wrote a book report on this book, which I entitled Rafts and Tsunamis, with the Ajijic Book Club in mind. My report on the book Incompleteness: The Proof and Paradox of Kurt Gödel by Rebecca Goldstein, which I entitled Golden Goldstein and Gödel was likewise written with ABC in mind. The third book is The Accidental Universe: The World You Thought You Knew by Alan Lightman. He is a rare scientist for whom science is a spiritual experience. Here is a link to my review of his book.

Maria Popova, on her excellent website Brain Pickings, selected The Great Unknown as one of her 7 Favorite Science Books of 2017. Her colorful review of the book is entitled Mathematician Marcus du Sautoy on the Unknown, the Horizons of the Knowable, and Why the Cross-Pollination of Disciplines is the Seedbed of Truth. She also reviews Gleiser’s book The Island of Knowledge: How to Live with Mystery in a Culture Obsessed with Certainty and Definitive Answers and Goldstein’s book Einstein, Gödel, and Our Strange Experience of Time: Rebecca Goldstein on How Relativity Rattled the Flow of Existence and Lightman's and Lightman’s book Alan Lightman on Our Yearning for Immortality and Why We Long for Permanence in a Universe of Constant Change.

We can think about human knowledge in various ways. The aggregate of all human knowledge is much greater than what any one person knows. Exceptional people like Marcus du Sautoy, Marcelo Gleiser, Rebecca Goldstein and Alan Lightman are very knowledgeable but can still only know a small fraction of aggregate human knowledge. Average and ordinary people, like me, know far less than people who are exceptionally intelligent and educated but we can learn much from them.