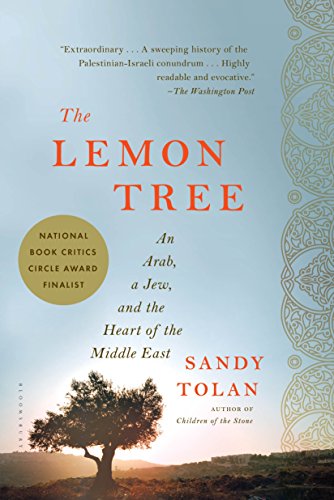

The Lemon Tree: An Arab, a Jew, and the Heart of the Middle East

from amazon.com

In 1967, Bashir Al-Khayri, a Palestinian twenty-five-year-old, journeyed to Israel, with the goal of seeing the beloved old stone house, with the lemon tree behind it, that he and his family had fled nineteen years earlier. To his surprise, when he found the house he was greeted by Dalia Ashkenazi Landau, a nineteen-year-old Israeli college student, whose family fled Europe for Israel following the Holocaust. On the stoop of their shared home, Dalia and Bashir began a rare friendship, forged in the aftermath of war and tested over the next thirty-five years in ways that neither could imagine on that summer day in 1967. Based on extensive research, and springing from his enormously resonant documentary that aired on NPR's Fresh Air in 1998, Sandy Tolan brings the Israeli-Palestinian conflict down to its most human level, suggesting that even amid the bleakest political realities there exist stories of hope and reconciliation.

https://www.amazon.com/Lemon-Tree-Arab-Heart-Middle-ebook/dp/B002UM5B8C

Author: Sandy Tolan

Sandy Tolan is a best-selling author, and an award-winning radio and print journalist who reports on and comments frequently about Palestine and Israel.

He is a professor at the University of Southern California (USC)’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism in Los Angeles. He is a co-founder of Homelands Productions, which for 25 years has produced international documentary and features for public radio.

Reviewed by: John Stokdijk

In the introduction to THE LEMON TREE An Arab, a Jew, and the Heart of the Middle East by Sandy Tolan, he writes:

I grew up with one part of the history, as told through the heroic birth of Israel out of the Holocaust.

As a teenager I already had a growing interest in world affairs. The conflict between Jews and Arabs in Palestine is one of the most difficult geopolitical challenges of my lifetime. I probably read about the Six Day War of 1967 in Time magazine, although I have no memory of doing so. I do remember having the same attitude as Tolan early in my life. However, I now share Tolan’s current perspective:

But as generations of historians have since documented… the actual history of the two peoples' relations is far more complex, not to mention richer and more interesting.

THE LEMON TREE is the intertwined story of Dalia Eshkenazi, a Bulgarian Jew, and Bashir Al-Khairi, a Palestinian Arab. The book is not only a very human story of two families but is also a good history of one aspect of the Middle East conflict, the issue of the Palestinian refugees and their right of return. Viewing history through the eyes of real people adds much to the cold facts.

In his Author’s Note, Sandy Tolan expresses his dedication to extensive research and he conducted hundreds of interviews over a period of seven years. The Bibliography and Source Notes at the end of the book are comprehensive. His intention is to “help build an understanding of the reality and the history of two peoples on the same land.” Understanding, says Tolan and I agree, “can only come from a recognition of each other's history.”

I was taken by surprise when I read the story of the Bulgarian Jews, one which I had never before encountered. Bulgaria was dominated by Hitler’s Germany during WWII but it was the only such country which did not send its Jews to the death camps. Consequently, 47,000 Bulgarian Jews escaped the Holocaust, an incredible story.

Born in 1947 in Bulgaria, the following year Dalia moved with her parents to the new state of Israel. She grew up to become an unusually curious and thoughtful teenager. She wondered why she, a Jew, was being raised in what was clearly a beautiful Arab house. In an interesting twist of fate, one day a previous occupant of the house knocked on the door. That was the beginning of the intertwined story of Dalia Eshkenazi and Bashir Al-Khairi.

In 1936 Ahmad Khairi built a home for his family in al-Ramla, an Arab town located north of Jerusalem. And there Bashir was born in 1942. In 1948 there was a war called the War of Independence by the Jews and called the Catastrophe by the Arabs. For safety reasons Ahmad Khairi moved his family to Ramallah. Later that year the remaining Arabs were expelled from al-Ramla.

The story of Dalia and Bashir unfolds over subsequent decades against the backdrop of the dramatic events of this part of the Middle East. They live very different lives and have very different perspectives on the unresolved Israeli-Palestinian conflict. There is no happy ending to this story.

In some ways, the specifics of Bashir’s decision to maintain silence with Dalia do not matter. They are symptomatic of a steady deterioration of relations between Israelis and Palestinians...

There are a number of significant sub-plots and themes in THE LEMON TREE:

seemingly endless wars and terrorism

the house, which became Open House, with a lemon tree in the backyard

the changes in the perspectives of Dalia as she moves through life

why Bashir kept his left hand in his pocket

the open letter that Dalia writes.

Sandy Tolan does not express his personal opinions on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He makes no predictions about the future of this troubled region. Personally, I see no end to this conflict and I will be surprised if it is resolved in my lifetime.

At its meeting on March 27th, twelve ABC members had an excellent discussion of The Lemon Tree. Program Leader Allison Quattrocchi had travelled to Israel, Jordan and Egypt in December, 2017 which stimulated her desire to learn more about what she had experienced. One member had lived in Jordan for two years and another member had lived in the United Arab Emirates for eight years. One member was herself a Jew. Another member had been married to a Jew and another member had had Jewish boyfriends. These diverse experiences added much to the discussion.

A significant learning for me was the insight that the Palestinian Arabs are themselves generally looked down upon by other Middle Eastern Arabs which perhaps explains the lack of support for their cause and their needs.

Program Leader Allison Quattrocchi had provided discussion questions in advance and below are my prepared answers.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS FOR “THE LEMON TREE”

1. Did you learn things from the book that you did not know about the Israeli/Palestinian conflict? If so, what stands out? Did this book alter your perspective regarding or understanding of the conflict?

From time to time I have studied this conflict and I have discussed it with a good friend in a string of emails. I learned some new details from the book but I was already familiar with most of the major geopolitical events. The book deepened my understanding but did not alter my opinions. However, the story of the Bulgarian Jews was something I had never before encountered.

2. The book describes Dalia as carrying “an extraordinary legacy” with her to Israel from 1948. What was that legacy?

Most Jews carry an extraordinary legacy. They are an ancient people who were scattered to the ends of the earth. Yet somehow many Jews never let go of their religious or cultural heritage. That legacy included an affinity of their ancient homeland.

3. Would you describe Dalia and Bashir as extraordinary human beings? If so, why?

Dalia strikes me as an extraordinary person because of her ability to think independently from a very young age. Unlike most ordinary human beings, she was able to question assumptions taken for granted by those around her. Bashir does not seem extraordinary, but I do not mean this as a criticism.

4. Can you empathize with Bashir’s insistence on and sacrifice for “the right of return”? Why was this such a singular focus for Palestinians during this time?

I cannot imagine what it would be like to be forced out of my home and off of my land. What would such an experience do to me? I can only be grateful for the time and place of my own birth. But it is difficult for me to understand how any reader of The Lemon Tree could not have empathy for Bashir.

5. What did you think about Dahlia’s published open letter to Bashir and his response?

Dalia's letter is available online on the Open House in Ramle website and includes a picture of Dalia herself. I think her letter is a reasonable appeal to Bashir, a realistic pathway to potential peace. But her thoughtful approach is not that of the Government of Israel and perhaps not the approach of the majority of Israeli citizens. I find it easy to understand the passion of Bashir in his reply. But justified passion is not a pathway to peace. Unfortunately, the facts on the ground carry more weight than the reason of Dalia and the passion of Bashir.

6. When they finally meet again, they find that their political differences are as great as ever, but that their personal relations are as warm as ever. How does one explain that?

I did not see their personal relationship as warm and certainly not at the end of the book.

7. Near end of book, Dalia says “our enemy is the only partner we have.” What does she mean by that?

Dalia understands, remarkably, that hope for peace in Palestine will come when Jews and Arabs thoroughly understand why they each claim the same land, why they are enemies.

8. Does the lemon tree hold any particular symbolism?

The lemon tree was real and, significantly, grows on the land around the house. It has real value to the occupants of the house. It is not symbolic of anything more but it does make for a clever and appropriate title to the book.

9. Is the conflict between the Israelis and the Palestinians primarily a religious conflict or primarily a struggle by both sides for survival and human dignity? Do you think its nature has changed over the years?

The conflict is very complex and religion is one important element. The struggle for survival and for dignity are also important elements. It is also a nonreligious geopolitical conflict with some similarities to other clashes elsewhere, expressing a human instinct to fight unless tamed by civilization . At its core, in my opinion, it is a conflict driven by the very human need for identity. Peace will come if, somehow, the identity of being human transcends the need to be a Jew or a Palestinian Arab.

10. This book has been described as optimistic. In your opinion, is it? And, if so, what makes it so?

Perhaps some readers are projecting their personal optimism onto the book. I see no basis for optimism in the book nor in the current situation. I have hope based on my choice to be idealistic but hope and optimism are not the same.

11. The book was published in 2006. Is the situation today different? Do you have any thoughts about the future of Israel and Palestine?

My version of the book includes a brief afterward with a continuation of the story up to 2014.

I have many thoughts about the future of Israel and Palestine and I will continue to be an interested observer of this extremely difficult situation.

Reviewed by: Karl Homann

POSTSCRIPT TO ABC DISCUSSION

While The Lemon Tree by Sandy Tolan certainly tries valiantly to strike a balance between the warring fashions of Jews and Palestinians, I was somewhat troubled by our discussion on Tuesday, which favoured the Palestinians as the victims and declared the Jews as the victimizers. Therefore, I would like to clarify my own position and draw some parallels between “Zionism” and similar political movements of the past.

In doing so, I have placed my own comments in longhand and information from various sources on a given subject indented and in italic.

ZIONISM

Zionism is the national movement of the Jewish people that supports the re-establishment of a Jewish homeland in the territory defined as the historic Land of Israel (roughly corresponding to Canaan, the Holy Land, or the region of Palestine).

It emerged as a political movement in 19th century Europe aimed at establishing a Jewish homeland and combating ant-Semitism.

The Balfour Declaration of 1917 gave British support to the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine. (Previously, Palestine had been under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, centered in Istanbul, for 400 years since 1516.)

Hence, if Palestinians claim and insist on their right to “return”, I ask, to return where? To the “Palestine” of the Ottoman Empire or the British Mandate?

Until 1948, the primary goals of Zionism were the re-establishment of Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel, ingathering of the exiles, and liberation of Jews from the anti-Semitic discrimination and persecution that they experienced during their diaspora. Since the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, Zionism continues primarily to advocate on behalf of Israel and to address threats to its continued existence and security.

A religious variety of Zionism supports Jews upholding their Jewish identity defined as adherence to religious Judaism, opposes the assimilation of Jews into other societies, and has advocated the return of Jews to Israel as a means for Jews to be a majority nation in their own state. A variety of Zionism, called cultural Zionism, founded and represented most prominently by Ahad Ha'am, fostered a secular vision of a Jewish "spiritual center" in Israel. Unlike Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, Ahad Ha'am strived for Israel to be "a Jewish state and not merely a state of Jews".

Advocates of Zionism view it as a national liberation movement for the repatriation of a persecuted people residing as minorities in a variety of nations to their ancestral homeland.

Critics of Zionism view it as a colonialist, racist and exceptionalist ideology that led to violence during Mandatory Palestine, followed by the exodus of Palestinians, and the subsequent denial of their right to return to property lost during the 1948 war.

Theodor Herzl (May 2, 1860 – July 3, 1904)

Herzl was an Austro-Hungarian journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern political Zionism. Herzl formed the Zionist Organization and promoted Jewish immigration to Palestine to form a Jewish state. Though he died before its establishment, he is known as the father of the State of Israel.

... Herzl is specifically mentioned in the Israeli Declaration of Independence and is officially referred to as "the spiritual father of the Jewish State", i.e. the visionary who gave a concrete, practicable platform and framework to political Zionism…

A philosophy for a homeland

In Der Judenstaat, Herzl writes:

"The Jewish question persists wherever Jews live in appreciable numbers. Wherever it does not exist, it is brought in together with Jewish immigrants. We are naturally drawn into those places where we are not persecuted, and our appearance there gives rise to persecution. This is the case, and will inevitably be so, everywhere, even in highly civilised countries—see, for instance, France—so long as the Jewish question is not solved on the political level.”

The book concludes:

Let me repeat once more my opening words: The Jews who wish for a State will have it… We shall live at last as free men on our own soil and die peacefully in our own homes… The world will be freed by our liberty, enriched by our wealth, magnified by our greatness.

And whatever we attempt there to accomplish for our own welfare, will react powerfully and beneficially for the good of humanity.

1948 Palestine war

The 1948 Palestine war, known in Hebrew as the War of Independence or the War of Liberation and in Arabic as The Nakba or Catastrophe refers to the war that occurred in the former Mandatory Palestine during the period between the United Nations vote on the partition plan on November 30, 1947, and the official end of the first Arab-Israeli war on July 20, 1949.

Historians divide the war into two phases:]

1.

The 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine (sometimes called an "intercommunal war") in which the Jewish and Arab communities of Palestine, supported by the Arab Liberation Army, clashed, while the region was still fully under British rule. 2.

The 1948 Arab–Israeli War after 15 May 1948, marking the end of the British Mandate and the birth of Israel, in which Transjordan, Egypt, Syria and Iraq intervened in sending expeditionary forces that entered Palestine and engaged the Israelis.

Arab League strategic failure

… contingents of four of the seven countries of the Arab League at that time, namely Egypt, Iraq, Transjordan, and Syria, invaded territory in the former British Mandate of Palestine and fought the Israelis. They were supported by the Arab Liberation Army and corps of volunteers from Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and Yemen. The Arab armies launched a simultaneous offensive on all fronts, Egypt forces invaded from south, Jordanian and Iraqi forces invaded from east, while Syrian forces invaded from north. Co-operation among the various Arab armies was poor.

So, who is the aggressor?

In thinking about the Herzl Manifest of Zionism, I was reminded of an earlier manifest on another continent, the Manifest Destiny, both in terms of its objective and its language.

Manifest Destiny

Origen of the term:

This concept appeared first as “divine” destiny when Journalist John L. O'Sullivan… predicted in an article he wrote in 1839 a "divine destiny" for the United States based upon values such as equality, rights of conscience, and personal enfranchisement "to establish on earth the moral dignity and salvation of man".

Six years later, in 1845, columnist John L. O'Sullivan, wrote another essay titled “Annexation in the Democratic Review”, in which he first used the term “manifest destiny”. In this article he urged the U.S. to annex the Republic of Texas, not only because Texas desired this, but because it was "our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions". Overcoming Whig opposition, Democrats annexed Texas in 1845.

O'Sullivan's second use of the phrase became extremely influential. On December 27, 1845, in his newspaper the New York Morning News, O'Sullivan addressed the ongoing boundary dispute with Britain. O'Sullivan argued that the United States had the right to claim "the whole of Oregon":

“And that claim is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.”

The 19th century term manifest destiny thus became a widely held belief in the United States that its settlers were destined to expand across North America.

Historian Frederick Merk (Harvard University until 1956) writes, this concept was born out of "a sense of mission to redeem the Old World by high example ... generated by the potentialities of a new earth for building a new heaven".

Historians have emphasized that "manifest destiny" was a contested concept—pre-civil war Democrats endorsed the idea, but many prominent Americans (such as Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant) rejected it.

Historian Daniel Walker Howe writes, "American imperialism did not represent an American consensus; it provoked bitter dissent within the national polity ... Whigs saw America's moral mission as one of democratic example rather than one of conquest."

Historian William E. Weeks has noted that three key themes were usually touched upon by advocates of manifest destiny:

·

the virtue of the American people and their institutions; ·

the mission to spread these institutions, thereby redeeming and remaking the world in the image of the United States; ·

the destiny under God to do this work. The origin of the first theme, later known as American Exceptionalism, was often traced to America's Puritan heritage, particularly John Winthrop's famous "City upon a Hill" sermon of 1630, in which he called for the establishment of a virtuous community that would be a shining example to the Old World. In his influential 1776 pamphlet Common Sense, Thomas Paine echoed this notion, arguing that the American Revolution provided an opportunity to create a new, better society:

We have it in our power to begin the world over again. A situation, similar to the present, hath not happened since the days of Noah until now. The birthday of a new world is at hand...

This last statement, to me, sounds a lot like “Christian Zionism”.

In fact, Abraham Lincoln opposed the imperialism of manifest destiny as both unjust and unreasonable… and believed that each of these forms of patriotism threatened the inseparable moral and fraternal bonds of liberty and Union that he sought to perpetuate through patriotic love of country guided by wisdom and critical self-awareness.

John Quincy Adams, in 1811, wrote to his father:

The whole continent of North America appears to be destined by Divine Providence to be peopled by one nation, speaking one language, professing one general system of religious and political principles, and accustomed to one general tenor of social usages and customs. For the common happiness of them all, for their peace and prosperity, I believe it is indispensable that they should be associated in one federal Union.

To end the War of 1812 John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay and Albert Gallatin (former Treasury Secretary and a leading expert on Indians) and the other American diplomats negotiated the Treaty of Ghent in 1814 with Britain. They rejected the British plan to set up an Indian state in U.S. territory south of the Great Lakes….

Adams, Clay and Gallatin explained the American policy toward “acquisition” of Indian lands:

… [We] will not suppose that… [England] will avow, as the basis of their policy towards the United States a system of arresting their natural growth within their own territories, for the sake of preserving a perpetual desert for savages.

A shocked Henry Goulburn, one of the British negotiators at Ghent, remarked, after coming to understand the American position on taking the Indians' land:

Till I came here, I had no idea of the fixed determination which there is in the heart of every American to extirpate the Indians and appropriate their territory.

****

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on Israel & Zionism

“When people criticize Zionists, they mean Jews. You’re talking anti-Semitism.”

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., October 27, 1967, at a Civil Rights rally in Boston

“Peace for Israel means security, and we must stand with all our might to protect her right to exist, its territorial integrity and the right to use whatever sea lanes it needs. Israel… a marvelous example of what can be done, how desert land can be transformed into an oasis of brotherhood and democracy. Peace for Israel means security, and that security must be a reality."

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., March 25, 1968, Speaking at the 68th annual convention of the Rabbinical Assembly

PERSONAL REFLECTION

My reason for posting the above is simply to supply more information on a complex situation because blaming one or the other party in the ongoing and, in my opinion, worsening conflict does not help in resolving the situation. Both people deserve the security of a homeland, and that can only be achieved in acknowledging the existence of the other and by directly negotiating between each other the terms of peaceful coexistence, without interference by any other biased or compromised country or institution.

I would point to the European Union as an example, which in a remarkable fashion achieved such coexistence among former mortal enemies. In today’s fractured world, the EU has become the “shining beacon on the hill” towards a path to peace among nations.

The primary purpose for the creation of a United Europe was peace, lasting peace among its neighbor states, not economic prosperity…

It emerged from the vision of those who chose to look beyond the narrow confines of the moment into the distant horizon, accompanied by an iron will, notwithstanding the endless hurdles and roadblocks along the way.

Today, the Union is sustained by political will… that was born of moral determination [not only] to bury the continent’s blood rivalries and [but also] to atone for its ethnic and religious persecutions – an exercise that has, by any historical measure, succeeded admirably.

Karl Homann