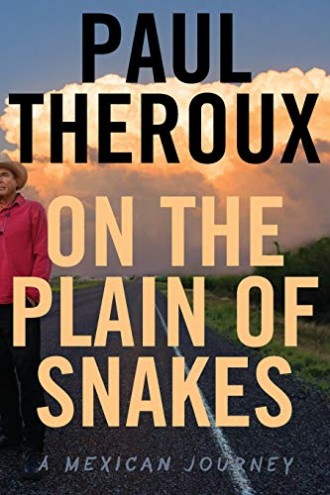

On the Plain of Snakes: A Mexican Journey

from amazon.com

Legendary travel writer Paul Theroux drives the entire length of the US–Mexico border, then goes deep into the hinterland, on the back roads of Chiapas and Oaxaca, to uncover the rich, layered world behind today’s brutal headlines.

Paul Theroux has spent his life crisscrossing the globe in search of the histories and peoples that give life to the places they call home. Now, as immigration debates boil around the world, Theroux has set out to explore a country key to understanding our current discourse: Mexico. Just south of the Arizona border, in the desert region of Sonora, he finds a place brimming with vitality, yet visibly marked by both the US Border Patrol looming to the north and mounting discord from within. With the same humanizing sensibility he employed in Deep South, Theroux stops to talk with residents, visits Zapotec mill workers in the highlands, and attends a Zapatista party meeting, communing with people of all stripes who remain south of the border even as their families brave the journey north.

From the writer praised for his “curiosity and affection for humanity in all its forms” (New York Times Book Review), On the Plain of Snakes is an exploration of a region in conflict.

Author: Paul Theroux

Paul Theroux is the author of many highly acclaimed works of fiction and nonfiction. Theroux holds honorary doctorates from three American universities and remains a highly sought-after speaker nationwide. “One of the most accomplished and worldly-wise writers of his generation” (The Times, London), Paul Theroux lives in Hawaii and on Cape Cod.

Reviewed by: Wendy Jane Carrel

Do you wish to experience Mexico authentically and not the Mexico of resort destinations? This book by revered travel writer Paul Theroux published in the fall of 2019 may be for you.

Theroux was 79 years of age at the time of writing. He states he offers an “old gringo” perspective. He compares his recent journey, partly by car, with one over 20 years ago, also by car and also solo. Other than Latin American history scholar Lesley Byrd Simpson’s Many Mexicos (1941), Theroux’s is now a new favorite of mine about the land and its people. I recommend it.

Note: Both Simpson and Theroux outline the paradoxes of Mexico, the diversity from state to state of food-geography-culture-language, and challenges you may encounter in order to survive.

“Mexico is not a country. Mexico is a world,” Theroux begins. He continues, "the country has 26 species of Mexican rattlesnakes." (The book title may not be an accident).

I have traveled to some of the small villages and bigger cities Theroux writes about. I had a big smile of familiarity on my face learning what he discovered. Though I have not experienced the underbelly the way he has, or dealt with corruption and Mexican police the way he has, the environments and mind-sets he exposes are vivid, memorable, and from my experience, spot on. I appreciated each of his insights and observations.

He captures heart-wrenching migrant border stories, the efforts of non-profits to provide humanitarian relief, images of barbed wire fences and walls, activities of border patrols, something about the Mormons in Chihuahua, as well as the degradation and violence perpetrated by “coyotes” and drugs cartels.

He manages to interweave the sad with the quirky and the meaningful.

He shares about eating delicacies (he’s brave), learning more Spanish, teaching bright young Mexican authors as a guest lecturer, observing the privilege and poverty of expat haven San Miguel de Allende, and reading worthy books by others about Mexico and so much more.

A good read!!!!!

An aside: if you happen to have an interest in the Virgin of Guadalupe and Mexico City Eryk Hanut’s hilarious adventure in The Road to Guadalupe: A Modern Pilgrimage to the Goddess of the Americas (Penguin Putnam 2001) is highly recommended. It’s been a favorite book all these years. It is out-of-print but used copies may be found at Amazon, EBay, and Thriftbooks.

Reviewed by: John Stokdijk

There is an uncommon aspect of the nonfiction book On the Plain of Snakes: A Mexican Journey by Paul Theroux that I much appreciated. In works of fiction an author can write from the subjective perspective of a character. That is never appropriate in nonfiction unless, of course, an author writes from his or her personal viewpoint. That is what Theroux does. Consequently, we can get inside his head as he travels inside Mexico.

We learn about how anxious Theroux was when stopped by police. We share his joy as he conducts a workshop in Mexico City for Mexican writers. We feel his vulnerability as a student in an intermediate level Spanish class.

At about the three-quarter mark, Theroux shares the purpose of his books, the purpose of his life.

I have spent my reading and writing life, and my traveling, trying to see things as they are—not magical at all, but desperate and woeful, illuminated by flashes of hope.

The result is a book about the real Mexico, not for everyone. One Ajijic Book Club member, someone who is also a good friend, soon put the book down, unwilling to cope with the content. Early in the book Theroux, who is also a researcher, describes cartel activity in graphic detail. Cartel business, the battles for control of unlawful border crossings of humans and drugs, is Mexico at its worst. It is not easy to read about Jalisco New Generation, the cartel that operates in the state where I live.

Although I was unfamiliar with Paul Theroux, I immediately admired his style. He is a descriptive writer, beyond skillful, an artist with words. At times I reread certain paragraphs just to enjoy their beauty.

Another reason I enjoyed this book was its subject matter, Mexico, the country I have chosen for retirement, the final chapter of my life. Theroux writes about places I have been - Mexico City, San Miguel de Allende, Puerto Vallarta, Mazatlán and more. While I went primarily as a tourist, Theroux was an investigative journalist and I learned a lot from him.

Four years ago, my wife Pat and I drove to Laredo, Texas for a meeting at the Mexican consulate office. Theroux travelled on some of the same roads that we did. Again, I valued his comments about Saltillo, Monterrey and Nuevo Laredo.

Paul Theroux was born in 1941 and with self-deprecating humor he describes himself as an old man, something he seems to be completely at peace with.

In the casual opinion of most Americans, I am an old man, and therefore of little account, past my best, fading in a pathetic diminuendo while flashing his AARP card; like the old in America generally, either invisible or someone to ignore rather than respect, who will be gone soon, and forgotten...

Naturally, I am insulted by this, but out of pride I don’t let my indignation show. My work is my reply, my travel is my defiance. And I think of myself in the Mexican way, not as an old man but as most Mexicans regard a senior, an hombre de juicio, a man of judgment... But “Stand aside, old man, and make way for the young” is the American way.

Indeed, Theroux seemed to me to be a man of judgment, a wise man sharing insights gained over a lifetime of travel. I was expecting to read just a travel book but On the Plain of Snakes is much more than that. What the book became in Part Four was a big surprise, as was my personal reaction, and I will write about that later in this report.

This book will be of interest to those learning Spanish, something I have given up on. Theroux often uses and explains Spanish words which I do not absorb and retain. But Pat continues to study Spanish and I sent her some particularly colorful paragraphs including these:

We talked about words. Rosi said, “Gilipollas is used in Spain, not here. When we want to say ‘asshole,’ we say pendejo or cabrón, but que cabrón can be praise, too.” “What kind of cabrón is Donald Trump?”... “Give me a word,” I said. “Mamón,” she said. “Thinks he’s better than anyone.” Mamón is cocky. The literal meaning is unweaned, still suckling. But in colloquial Mexican Spanish it has a much broader meaning, implying conceited, idiot, scrounger, dickhead, mooch, jackass.

On the Plain of Snakes is a history lesson. I learned a lot about NAFTA and its unintended or disregarded consequences in both the United States and Mexico. Although superseded by USMCA, much of this story remains to be told in future years.

In Ajijic I often walk on a street named Lázaro Cárdenas. From the book I learned that he is regarded by many as Mexico’s best President. A quick look in wikipedia informed me that his term was long ago, from 1934 to 1940.

Paul Theroux is obviously an avid reader and a literary critic. This aspect of his book was of little interest to me as I was mostly unfamiliar with the works he commented on and I recognized only one name, D. H. Lawrence. But for those interested, On the Plain of Snakes can be a useful guide to further reading about Mexico.

In Mornings in Mexico, D. H. Lawrence recounts his walk to Huayapam… Lawrence was one of those highly absorbent few upon whom nothing is wasted… Less than three months in Oaxaca and he emerged with a full-length novel, a number of short stories, a dozen essays, and some translations.

Theroux travelled in Mexico in 2017 and 2018 and his resulting book was published in October 2019 and it includes a recent dark event. In considerable detail he tells the story of the killing on September 26, 2014, of 43 male and female students in the state of Guerrero. Living in the wonderful bubble of Lakeside, this extremely violent matter quickly faded from my mind. But it will not soon fade from the memories of many Mexicans.

One does not need to live long in Mexico to become aware of its most popular saint, Our Lady of Guadalupe. But Theroux gives us more. And reading about the growth of a cult is concerning.

Saint Jude Thaddeus, the patron saint of lost causes, last resorts, long shots, and dead ends, and perhaps because of the hope his image offers to desperate people, a popular saint in Mexican hagiology… Saint Jude is the second-most-popular saint in Mexico… (But both of these saints have heavy competition in popularity from Santa Muerte, the robed skeleton whose bony image and lipless grin is everywhere.)

The Santa Muerte cult, in its florid, more macabre form, is more recent, and the present day has seen a great resurgence of followers, especially among criminals. An elaborate Santa Muerte shrine (offerings of fruit, mescal, and money) had been found in 2002 in the house of a Gulf cartel boss, Gilberto García Mena (El June), according to Diego Osorno in his account of cartel violence, The War of the Zetas.

One of the themes in this book about the real Mexico is the low wages paid to Mexicans, both the undocumented working in the USA, those working in factories in their homeland and, inevitably, at the bottom of the ladder, the indigenous. I write this with the understanding that I am complicit in this systemic abuse. I benefit from cheap products and cheap produce with only a little knowledge of what occurs at every step of a long supply chain.

...in Fresno County.., 98 percent—most of them migrants, working in the fields, a great proportion undocumented. “Harvesting lettuce, we got about $400 a week. It cost us around $180 a week for room and food and expenses,” he said. “It was very hot, sometimes over a hundred degrees. It was no better later, in Santa Rosa, picking grapes—we got about $1,100 every two weeks.”

Attracted by the low wages in Reynosa (most employees start at $10 a day), hundreds of American and European factories operate there, and as many as 100,000 workers live in colonias (communities) around the town.

It took her a week to make a box with a lid, and for this she was paid 1,500 pesos, about $75, a good wage by local standards,

Since moving to Mexico from Canada eight years ago, I have been slowly gaining an awareness for the Mexican attitude towards death. My appreciation was strengthened by Theroux’s book. Those of us from cultures of denial can learn much living here. In a book with so much darkness, it was refreshing to see a bright light on a positive approach to a brutal human reality.

It is the Mexican boast that the gringo denies death, or has a horror of it, or in Europe sees death as tragic or romantic. “But during Mexico’s twentieth century,” writes Lomnitz, “a gay familiarity with death became a cornerstone of national identity.”

All these Mexican speculations seem true to me—death as a party, a plaything, a protest, a somber ritual.

But it was not a Mexican intellectual who summed up for me the ambiguities in the Mexican relationship to death. It was Muriel Spark, in her novel Memento Mori: “If I had my life over again I should form the habit of nightly composing myself to thoughts of death. I would practice, as it were, the remembrance of death. There is no other practice which so intensifies life. Death, when it approaches, ought not to take one by surprise. It should be part of the full expectancy of life. Without an ever-present sense of death life is insipid.”

I am writing this while in quarantine due to the coronavirus pandemic. Daily I am watching the worldwide Covid-19 death count mount. Like Spark, I feel that my life has intensified in several positive ways, including my engagement with this book.

As I noted earlier, I was taken by surprise by Part Four - The Road to Nueva Maravilla. I have read only a couple of books about Mexican history so I got quite a lesson. And I was unprepared for my personal emotional reaction.

The Triqui people are an indigenous group of about twenty thousand fluent speakers who live in and around San Juan Copala, a small town in the municipality of Santiago Juxtlahuaca, in the mountains to the west of Oaxaca state. San Juan is about eighty miles from Oaxaca city as the crow flies and many more miles by the winding roads. The tenacious Triqui decided that they had had enough of being cheated, sidelined, and ignored by the federal government and the Oaxacan state government. In 2006, inspired by the 1994 uprising of the Zapatistas in Chiapas, the Triqui distanced themselves from the Mexican state and declared the Autonomous Municipality of San Juan Copala.

I had never heard of Comandante Marcos, supreme leader of the Zapatista. But Paul Theroux had and he had received an invitation “on behalf of Comandante Marcos, supreme leader of the Zapatistas, whether I would be interested in attending a Zapatista event, announced as a “Conversatorio” of the EZLN, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation.” The book had taken an unexpected revolutionary turn!

...From my first glimpse in the news in 1994 of the masked figure of Subcomandante Marcos leaving the Lacandón jungle and appearing in San Cristóbal de las Casas on horseback, under the banner of the Ejército Zapatista Liberación Nacional, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, I had wanted to meet him and to know more.

...no one had forgotten the abuses of the government or the revolutionary fervor of the Zapatistas, soon to celebrate their quarter century of dominance in Chiapas, and still masked.

As I read I felt myself embracing the rebel cause. There are not many revolutionary leaders that I admire but Comandante Marcos has become an exception. And I found the attitude of Paul Theroux inspiring. Perhaps for the first time in my life I personally feel a faint stirring of desire for revolution. Now, in what seems to be a liminal time, it seems clear to me that the Establishment is incapable of leading us to further progress, incrementalism is a path to failure and perhaps revolution is better than collapse.

Now I will turn to something pleasant. Soon after arriving in Mexico I acquired a taste for tequila. But only in the last year have I begun to enjoy mezcal. Theroux’s description of taking a drink is a representative example of his descriptive writing skill.

And we drank, the first sip a knife blade of liquid slipping down my throat and stinging my eyes, the second sip soothing the laceration of the first sip. The third sip induced a feeling of well-being, warming my face. The second cup percolated to my extremities, a relaxation of fingers and toes, a mollifying of the mind and spirit.

Paul Theroux is a man who can enjoy himself.

... the days I spent in Mazatlán were peaceful, strolling on the malecón—thirteen miles of seafront promenade—trying out the restaurants, swimming on the hot afternoons, and at night smiling at the frenzied dancers in the joints in the seaside clubs... That was the best of Mexico for me—inexpensive meals that were delicious, cheap hotels that were comfortable, and friendly people who, out of politeness, seldom complained to outsiders of their dire circumstances:..

Of course the book explains its title, On the Plain of Snakes. The Mexican flag features both the eagle and the snake. Theroux explains this symbolism by quoting his Mexican writer friend, Diego Olavarría, who tells him this:

“Many places in Mexico have the serpent in their names: Coatzacoalcos, Coatepec. And ‘Cancún,’ in Maya, means Nest of Serpents.” And he elaborated: “Although our foundational myth, and our coat of arms, suggests that snakes are forces of evil that must be devoured by the virtuous eagles, the truth is more complicated than that. The eagles soar in the sky alone, but we Mexicans share the land with snakes.”

Had Pat read this book years ago she probably would have refused to move here. If my friends and family were to read this book, they would probably refuse to visit us. But we and thousands of other expats have very good lives here. We live in a very pleasant bubble we call Lakeside. It is easy here to soar with eagles and avoid the snakes.